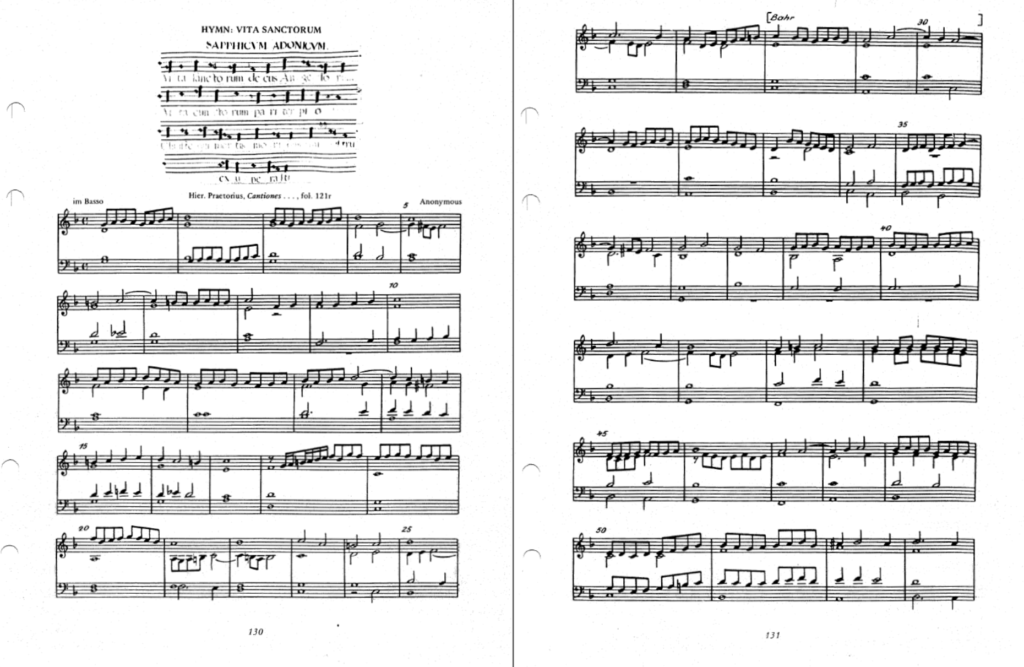

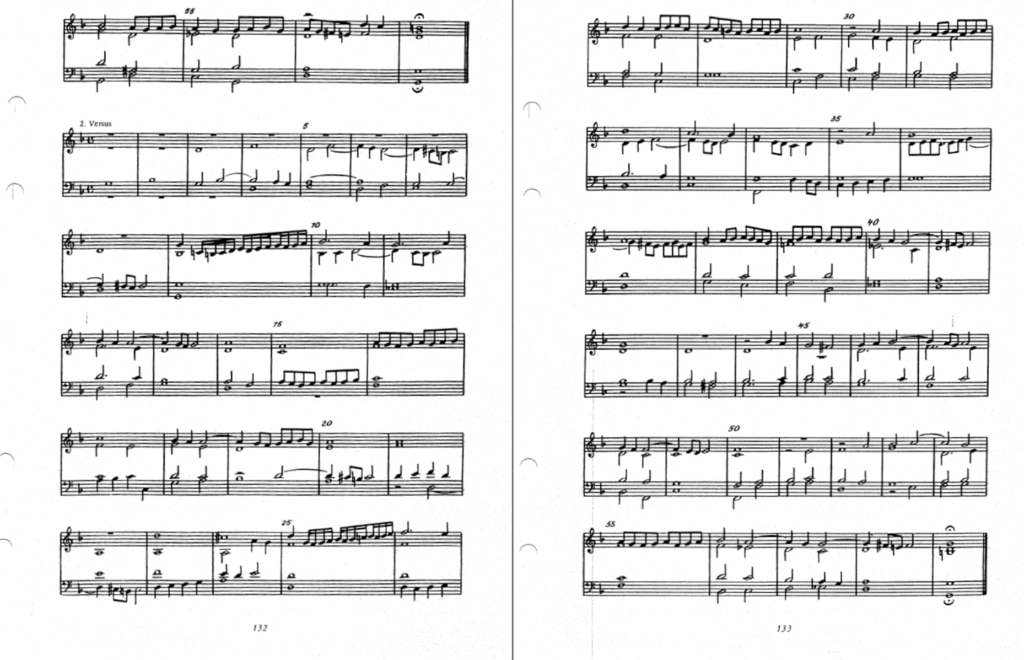

below the original (scan from the tabulature) and the transcription by Jeffery T. Kite-Powell in The Visby(Petri) Organ Tablature. Investigation and Critical Edition, Heinrichshofen’s Verlag, Wilhelmshaven, 1980, p. 130-134.

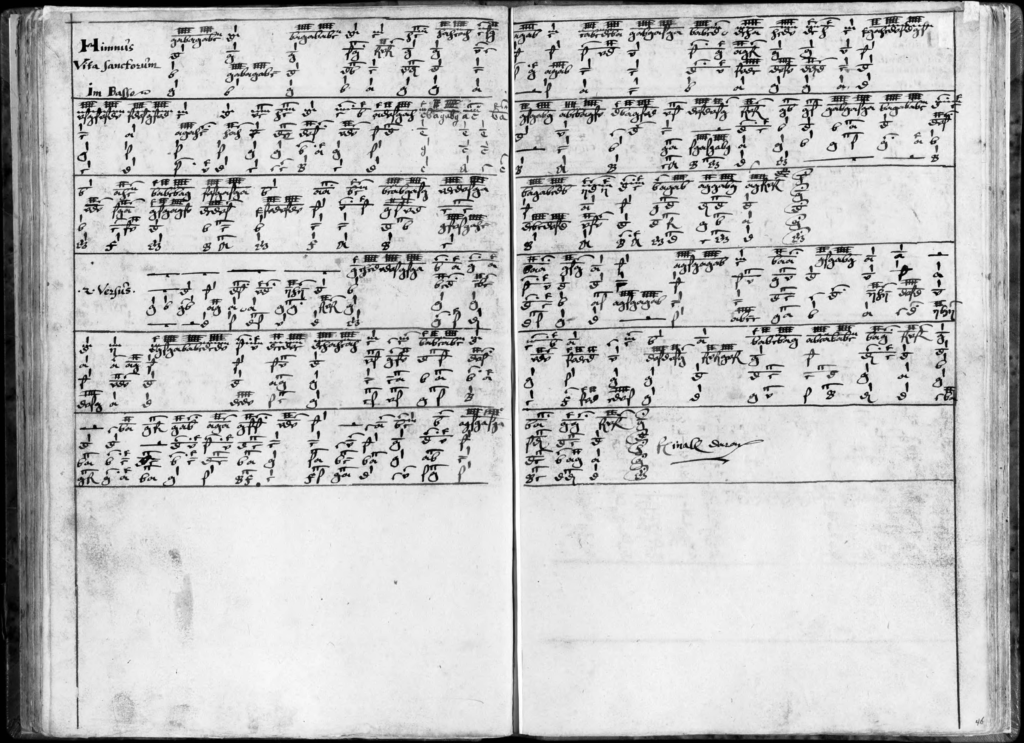

Tabulature

- Himnis Vita Sanctorum im Basso

- 2. versus

Transcription

Latin Mass in Protestant Germany?

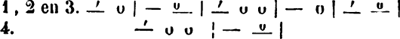

[Before continuing with some biographical information about the composer] One might wonder: how come, a Latin hymn in a Protestant service? Well, that’s nothing special. Quite common in the 17th century (and 18th, but less frequent). In particular the Evening-services and Early Morning: the Vespers and Matins. Culture, education and civilisation were based on ‘Latin’. The hymn in question – christe sanctorum decus angelorum – is a ‘make-over’ of the old hymn for Michaelmas (Hrabanus Maurus, early 9th Century), removing the ‘superstitious’ and elements from the text, replacing the direct invocations of the Angel(s) by a more general invocation in which the angels (Michael, but also Raphael) are ‘means’ used by God to protect humans. For those interested: I copied the entire ‘service’ for a LATIN Vesper for Saint Michael’s day on a separate page. You’ll find the complete hymn text there as well. Praetorius uses the title of a Easter hymn (Vita sanctorum decus angelorum) with the same strophic and metrical scheme: the ‘Sapphic ode’: three long lines (Hexameters – sapphicum) concluded with a short one (adonicum). The ‘inserted picture’ on top of the transcription mentions the metrical genre: Sapphicum adonicum.

Hieronymus Praetorius

(b Hamburg, 10 Aug 1560; d Hamburg, 27 Jan 1629).

Composer, organist, copyist and music editor, son of Jacob Praetorius (c1530-1586). On his father’s death in 1586 he became first organist, and he held this post until his death. Three of his four sons were musicians too: The two most important ones: Jacob II, and Johannes ; the third son, Michael, published a five-part wedding motet at Hamburg in 1619 and died at Antwerp possibly in 1624.

All but five of Praetorius’s masses, motets and vocal Magnificat settings were published between 1616 and 1625 in Hamburg as a five-volume collected edition. 50 of his motets are polychoral compositions for eight to 20 voices divided into two, three or four choirs. They were among the earliest Venetian-inspired music to be published in north Germany and are Praetorius’s most progressive and important works. These are similar in style to the polychoral motets of Hassler, but the expression of the text is more vivid because Praetorius introduces greater contrasts of texture, harmony and rhythm. They are less homophonic than such works by many other composers because of the extensive use of imitation and the breaking up of basically chordal structures by rhythmically and motivically active inner parts.

In 1587 Praetorius compiled and copied a collection of monophonic German and Latin service music for the Hamburg churches, containing the chants for Matins, Mass and Vespers for the Sundays and feast days of the church year: Cantiones sacrae chorales (in the image above – the transcription – the ‘gregorian chant’ is copied from this publication). It may have served as the model for Franz Eler’s Cantica sacra (Hamburg, 1588), the contents of which are similar but not identical. Praetorius was also the chief compiler of the Melodeyen Gesangbuch (Hamburg, 1604), a collection of 88 four-part German chorale settings by the organists of the four largest Hamburg churches. It is the first German collection to specify organ accompaniment to congregational singing of chorales and includes 21 of his own harmonizations. The other three composers represented are Joachim Decker, Jacob Praetorius (ii) and David Scheidemann, father of Heinrich Scheidemann.

The only organ works definitely by Praetorius are a complete set of eight Magnificat settings in the Visby (Petri) Tablature, which were composed by 1611, an additional Magnificat in the first tone in the Clausthal-Zellerfeld Tablature, and two chorale settings. They are full-textured works, often in five real parts, and were certainly designed for a large organ, including pedal (the organ that Praetorius played at the Jacobikirche, Hamburg, is described by Michael Praetorius in Syntagma musicum, ii, Wolfenbüttel, 1618, 2/1619/R). NB: The present organ is a ‘revised’ (and ‘restored’) version of this organ according to the concept of Arp Schnitger. The eight Magnificat settings in the Visby Tablature are the earliest unified set of organ works by a north German composer. On stylistic grounds it is highly probable that Praetorius also composed almost all of the anonymous organ pieces – settings of hymns, sequences and Mass items – in the Visby Tablature. The case for his authorship is convincingly argued by Kite-Powell. If these works are indeed by him he must be considered the founder of 17th-century German organ music and, next to Michael Praetorius, the leading north German composer of the early 17th century.